If you occasionally consult books or articles on ACT, CBT, or the behavioral approach, you may have seen references to the theory of evolution from time to time. And perhaps these references may have surprised you. What does natural selection have to do with these stories of learning and psychological difficulties? It’s actually a story that has been going on for quite some time, first on a theoretical level, and more recently with concrete applications in clinical practice, as I do in my workshop Darwin as a clinical supervisor! – Mastering the evolutionary processes of Process-Based Therapy.

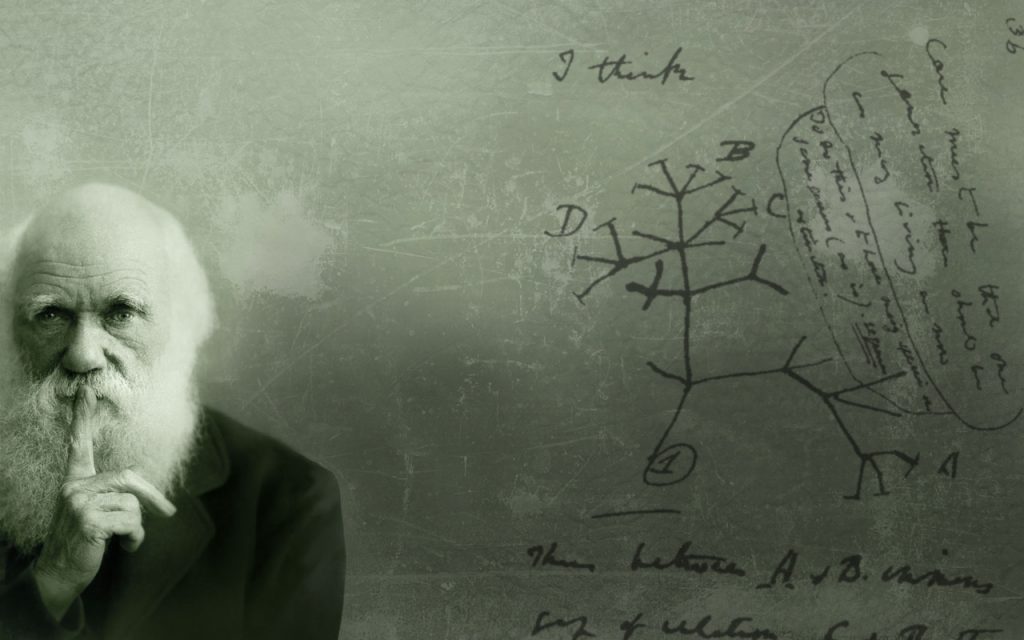

One of the first articles on this issue was published in the 1980s in the journal Science and was entitled Selection by consequences (Skinner, 1981). It draws a parallel between natural selection and operant learning. Natural selection, a principle proposed by Darwin to understand the evolution of species, is in fact selection by consequences, as is operant learning: it is because of their adaptation to their environment that individuals more or less manage to reproduce, and thus more or less transmit their characteristics to the next generation. Similarly, as the discovery of operant learning has shown, behaviors tend to be more or less reproduced according to their more or less appreciable consequences for the individual.

This selection by consequences acts on different “materials” (individuals or behaviors) and on different time scales (over a large number of generations for natural selection, or on the scale of a few seconds for operant learning), but it is always the same mechanism. Consequently, the three processes of evolution – variation, selection, transmission – totally apply to behaviors. Indeed, behaviors vary: we never behave the same way twice, there are always changes, even small ones. Behaviors are selected: they produce more or less appreciable consequences for the individual. Finally, depending on their consequences, the behaviors are more or less reproduced, in other words, we continue behaving the same way, or we stop. This is the theoretical parallel that has been proposed since then.

Except that this parallel did not, at the time, catch the attention of researchers in the field of the so-called “hard” sciences, who work on evolutionary processes. Perhaps the main reason is that for a long time evolutionary research focused on genes, which were considered the only selected material in the evolution of species. A purely genetic selection, and not a behavioral one, is what characterizes evolutionary psychology, which is very different from the approach I am talking about here (to differentiate the two approaches, read my blog post Beware, false cognate : evolutionary psychology). But all this is changing, since researchers in evolutionary sciences have perceived the importance of behavior in the evolution of species, and particularly in the evolution of humans.

The importance of behavior in the evolution of species is now recognized by modern evolutionary sciences, notably through the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. For example, being able to modify one’s environment – what is called “niche construction” – has repercussions on the evolution of the species. Beavers that block a river with tree trunks then live in an ecosystem close to that of a pond, which modifies the flora, thus their feeding, and finally their evolution. Human beings are of course champions of modifying their environment, and therefore of modifying their evolution… Discoveries in epigenetics have also shown that genes are not expressed in the same way depending on the context, for example on what we eat or our relationships with others. All these phenomena now lead us to consider psychology, as the study of behavior, as one of the evolutionary sciences.

There is then only one step, which we take without any problem, to consider that clinical psychology is an applied evolutionary science. Thus, it is important for us as clinicians to develop our knowledge of evolutionary processes, because these processes determine our patients’ behaviors as well as our own, and our adaptation to the contexts in which we live.

[Would this article interest someone in your network? Share!]